Forget Dracula and Frankenstein…as Hallowe’en looms up on us, Dr Katy Soar, Senior Lecturer in Classical Archaeology at the University of Winchester, digs deep to unearth the ancient roots of the horror story.

As an archaeologist who has edited several volumes of stories that revolve around the intrusion of the past into the present (my most recent being Return of the Ancients: Unruly Tales of the Mythological Weird in the British Library Tales of the Weird collection), I am fascinated by both the use of archaeology in horror, but also the archaeology of horror. Narrative tales that centre on supernatural beings have a long history, perhaps longer than you think. While horror might be considered a literary genre, a subsection of speculative fiction with its roots in the gothic tradition, and an aim to simply scare the audience, this view would preclude a much older and rich tradition.

Fear of the non-human, whatever it may be or whatever form it may take, has much deeper roots. For it seems that for as long as we have been human, we have been – or wanted to be – scared. H.P. Lovecraft noted that ‘fear is the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind’, and if we trace the origins of horror, it seems that he was right.

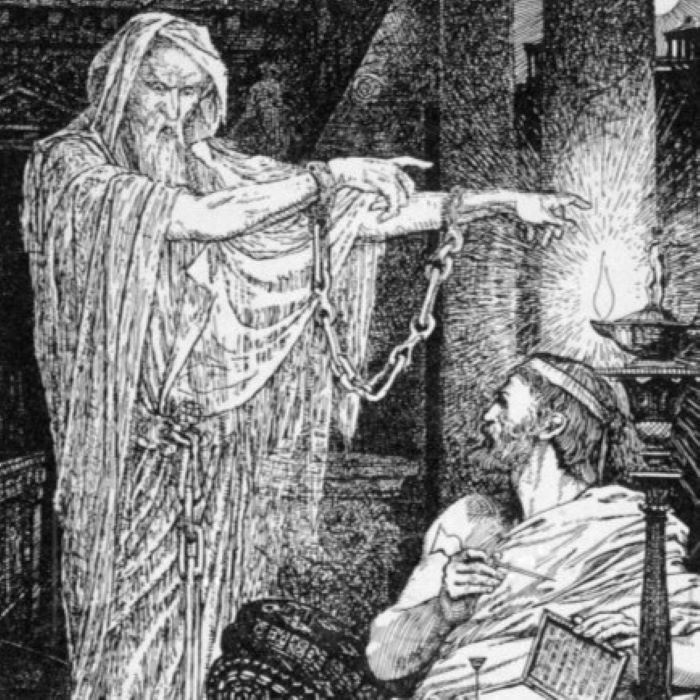

Our earliest haunted house story dates to c100- 109CE. The Roman writer Pliny the Younger recounts the tale of a Greek philosopher named Athenodorus, who rented a house in Athens which was haunted by the shackled and howling ghost of an old man. Digging at the spot where the ghost vanished every night, Athenodorus found the chained skeleton of a man; after giving the skeleton the proper burial and funeral rites, the haunting ceases.

Earlier than Pliny are the epics of Homer (thought to have been written in the late 8th century BCE), which, while not horror stories in themselves, nevertheless contain episodes of horror. In particular, The Odyssey, the poem recounting Odysseus’ epic wandering as he returns home to Ithaca after the Trojan war, is replete with staples of modern horror stories, such as giants, witches, sea creatures and ghosts.

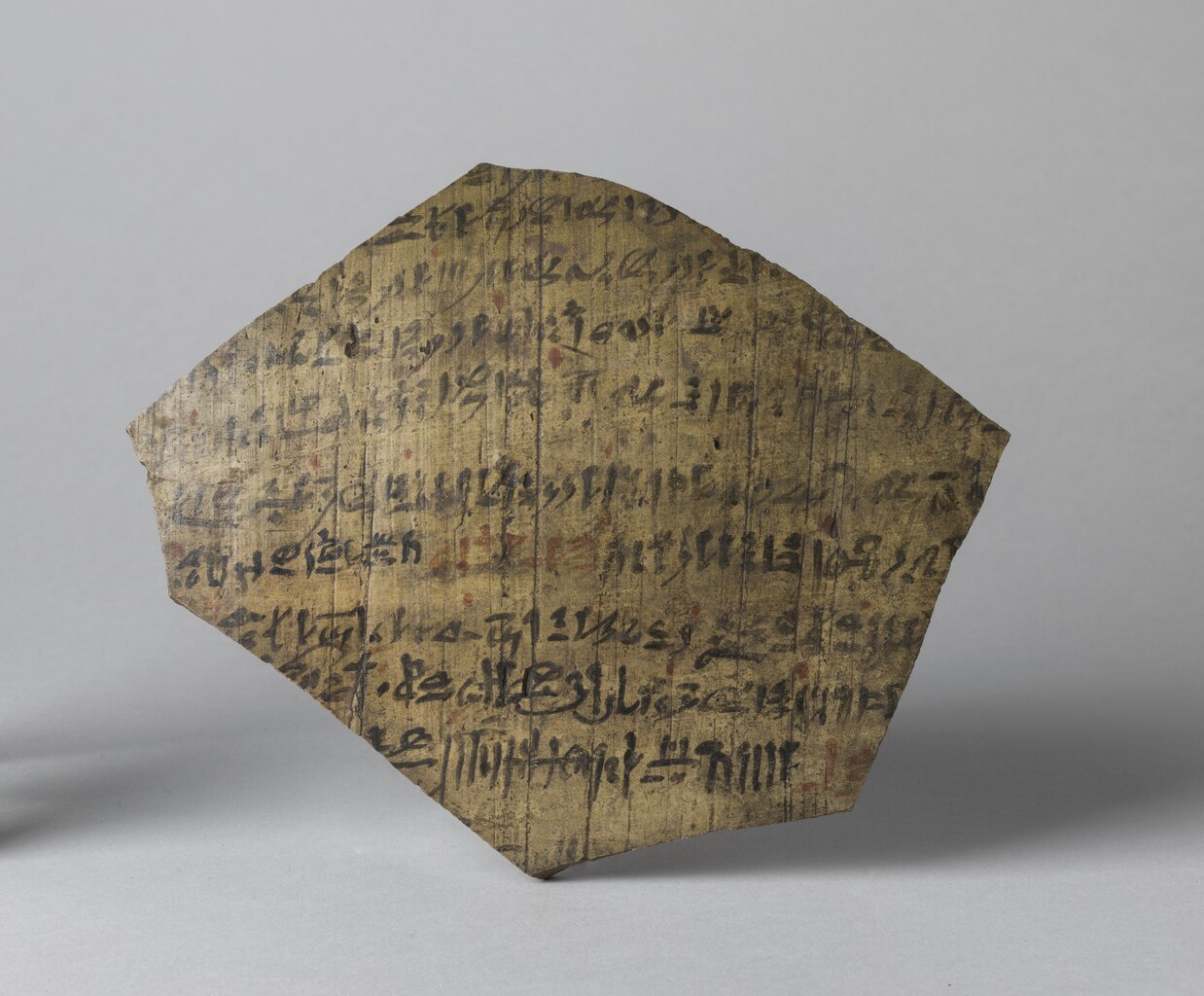

Part of the tale of Khonsemhab and the Ghost survives on the Turin fragment discovered in 1905

Before the Greeks, there were Egyptian horror tales, in particular the tale of Khonsemhab and the Ghost, which dates to the Ramesside period (c1300-1077 BCE). The eponymous Khonsemhab, a high priest of Amun, is visited by the ghost of a dead priest named Nebusemekh. Hearing that Nebusmekh’s tomb has fallen into disrepair, Khonsemhab weeps and promises to have the tomb restored.

Like Pliny, this story contains a moral message about the correct care of the dead. Before that, the cuneiform scripts of Mesopotamia, which first appeared on clay tablets as early as 3200 BCE, talk of ghosts. The Sumerian word for ghost was ‘gidim’, meaning the spirit of a dead person, and the oldest forms of the sign occur on clay tablets from about 2500 BCE. That ghosts were believed to be real and a threat to normal life is shown in the numerous references to the havoc they cause and ways to exorcise them recorded in tablets from the 3rd millennium BCE onwards.

Cuneiform was also used to relate the oldest written story yet known, a story that could also be considered the earliest horror or ghost story. This is the Epic of Gilgamesh, a poem written in the Akkadian language around 1700 BCE, which tells of the adventures of Gilgamesh, the semi-mythical 5th king of Uruk who reigned in the 26th century BCE, and his companion, the wild man Enkidu. While a myth, the story features many elements common to horror: ghosts, the giant ogre Humbaba, scorpion monsters, a monstrous bull, as well as proto-zombies. Ancient story tellers needed to make their audience pay attention to the moral and religious guidance and rules found within the tale, and it seems that they knew early on that narratives of the supernatural would be a crowdpleaser.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu slaying Humbaba (from Iraq, 19th–17th century BCE) in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin

Gilgamesh and Enkidu slaying Humbaba (from Iraq, 19th–17th century BCE) in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin

But we communicated long before we could write. Humankind’s earliest method of expression was art; the first definitive artwork created by homo Sapiens may date as far back as 73,000 years ago, when red ochre lines were daubed onto a rock in South Africa. Figurative art seems to date back at least to 40-50,000 years, and some of these figures may be supernatural beings.

A cave painting discovered in 2017 in a cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, recently dated to 51,200 years old, has been interpreted as a narrative scene in which a group of therianthropes hunt a pig with spears and ropes. The figures appear to have birds’ heads or animal tails and may be the earliest evidence for the representation of the supernatural or the non-human.

Who these beings are and how those that painted the scene viewed them remains impossible to tell, but – if this is truly a supernatural narrative - the desire and ability to imagine and record ideas of the supernatural or non-human sphere seem deeply ingrained in us as a species. Thus it seems that our very first recorded narratives, both in art and in literature, are ‘horror’ narratives. Horror may well be a tale as old as time.

Pictured top "Athenodorus confronts the Spectre". Engraving by Henry Justice Ford, from The Strange Story Book by Leonora Blanche Lang; Andrew Lang.

Sources:

Finkel, Irving. 2021. The First Ghosts. Most Ancient of Legacies. London: Hodder and Staughton

Oktaviana, A.A., Joannes-Boyau, R., Hakim, B. et al. 2024. Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago. Nature 631, 814–818

A longer version of this piece was originally published in the BFS Journal #26 (summer 2025): https://britishfantasysociety.org/coming-soon-bfs-journal-26/

Back to media centre