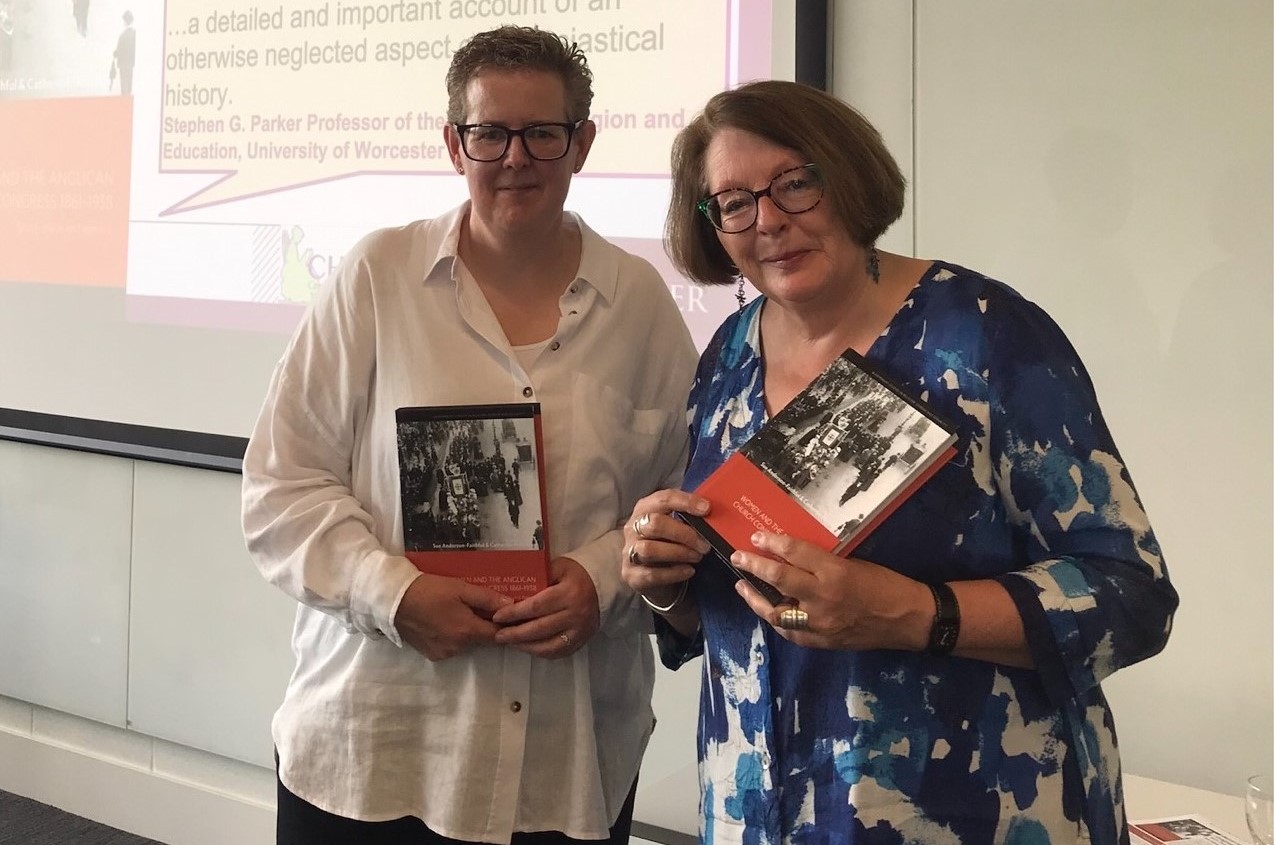

Sue Anderson-Faithful and Catherine Holloway at the launch of their new book

A new book by two academics from the University of Winchester shows that Victorian and Edwardian women were far more radical and enlightened than their big hats and skirts might suggest.

Employment rights, sex trafficking, race relations, education and alcohol abuse were just some of the issues dealt with by the ladies of the Anglican Church Congress.

The impact of the congress is examined in Women and the Anglican Church Congress 1861 -1938: Space, Place and Agency by Dr Sue Anderson-Faithful and Dr Catherine Holloway.

The pair launched their book at an event held at the University’s St Alphege Building recently.

The new book is the result of seven years’ research by Sue, a Senior Lecturer in Education Studies, and Catherine, a Lecturer in Education Studies and Childhood Studies.

The pair, both members of the University’s Centre for the History of Women’s Education, combed through official records, diaries, and old newspapers to capture the views and voices of the time.

Sue admits that Winchester and the surrounding area was a “hotspot for Victorian do-gooding ladies” several of whom feature in the book.

.jpg)

Laura Ridding, founder of the the National Union of Women Workers, Mary Townsend who founded the Girls' Friendly Society, and Mary Sumner, founder of the Mothers Union.

These included Laura Ridding, daughter of the first Earl of Selborne and wife of George Ridding the headmaster of Winchester College, who founded the National Union of Women Workers; Mary Sumner, a rector’s wife from Alresford, who founded the Mothers Union; and Mary Townsend, a botanist’s wife from Wickham, who founded the Girls’ Friendly Society.

Sue says: “Although a lot of their work prioritised chastity we must challenge the assumption that these were prudish Victorian ladies.

“They wanted to safeguard women, particularly unmarried women, and they wanted the same moral standards to apply to men as to women.”

At the first Anglican Church Congresswomen were only allowed to observe from the gallery but as time wore on they progressed from tea-makers to platform speakers.

Many of these influential women were connected to senior clergymen and the Congress helped them present their radical views to the male establishment.

“Because they were under the umbrella of the church it made them more acceptable and they were able to bring about change without being confrontational,” said Sue.

Although these do-gooding ladies may have been well-to-do, Sue and Catherine’s research shows that Congress audience was often packed with working class women keen to hear such speakers as trade unionist (and clergyman’s daughter) Gertrude Tuckwell, an opponent of sweated labour.

The Congress was the proverbial broad church and Sue explains that its female members were split over many issues including women’s suffrage and the ordination of women. However, they were all, in one way or other, out to improve the lot of women.

At the well-attended launch event the authors gave an entertaining Powerpoint presentation. A clip from a Pathe newsreel featuring a stray dog invading a conference procession was particularly well received.

Women and the Anglican Church Congress 1861 -1938: Space, Place and Agency is published by Bloomsbury.

Back to media centre